When the Save A Lot supermarket in Chicago’s West Garfield Park closed temporarily in early February, the West Side neighborhood of more than 17,000 residents was left without a grocery store. The Garfield Park Rite to Wellness Collaborative, which includes Rush University Medical Center, West Side United, local nonprofits and other community members, quickly organized food giveaways to ensure neighbors would have fresh produce, protein and other provisions.

“People shouldn’t have to travel outside their community to get healthy food,” said Julia Bassett, system manager of health and community benefits at Rush University Medical Center. "They resort to going to their local gas station, to go to maybe a liquor store ... or the most popular thing they do is go to a fast-food chain," she told ABC 7.

A person’s health and longevity are greatly affected by what are called the social determinants of health, which include access to nutritious food, said Bassett, who organizes urgent and ongoing programs to bring healthy food to the West Side residents who need it.

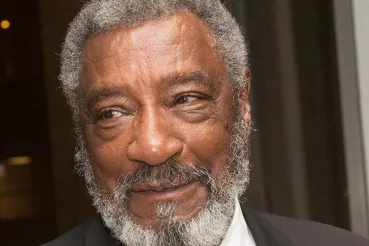

“Food is medicine,” said David Ansell, MD, MPH, senior vice president for community health equity for Rush University Medical Center. “I tell my patients to eat five fruits and vegetables a day, but fresh produce isn’t available to many of them.” Healthy food can be hard to find in many of Chicago’s West and South Side neighborhoods. Food deserts are a problem across the United States, affecting both urban and rural areas. But in Chicago, nearly all of the food deserts are in Black neighborhoods, aligning with the city’s traditional lines of segregation, according to a U.S. Commission on Civil Rights report. That report concluded that the Chicago food desert problem is not only a public health issue but is also a civil rights concern.

A growing problem

The COVID-19 pandemic and the rising food prices have made the problem worse, especially when access to food is disrupted by store closures.

On Feb. 21, Bassett, Ansell and dozens of volunteers from Rush, West Side United and the rest of the collaborative gathered in a lot next door to the shuttered Save A Lot at 420 Pulaski St. and prepared 100 packages of fresh food to feed a family of four for about a week and a half. Neighbors had already lined up before the food arrived. After the packages of chicken and ground beef, fresh fruits and vegetables, rice and other staples were ready, all 100 were gone within half an hour. The volunteers again handed out 100 packages of food on March 5; two additional distribution dates were canceled once the Save A Lot reopened.

Providing food to those who need it in an empty lot is a drill Rush and allied community groups have gone through before. Last fall, when the Aldi store in West Garfield Park closed unexpectedly, they organized six food giveaways, each providing enough fresh groceries to feed about 1,000 people for a week.

There is much more work to be done for West Garfield Park. “This is a drop in the bucket in addressing the neighborhood’s food insecurity,” Bassett said. Backed by a $10,000 grant from West Side United, Bassett has worked with Top Box, a nonprofit produce distributor, and Forty Acres, a West Side grocery startup, to supply the food giveaways at Save A Lot. Other donations funded the Aldi giveaways.

RUSH’s commitment

Chicagoans who live on the West Side have a life expectancy that is several years shorter than people who live in downtown and other more affluent neighborhoods. The disparity is greatest between West Garfield Park, with a life expectancy of 68 years, and the Loop, where the average is 82. Rush University Medical Center is committed to cutting that gap in half by 2030, as part of its core mission, Bassett said. The Medical Center invests in the West Side through its hiring and purchasing practices, education, health and volunteer initiatives, as well as food programs.

“We know where you live dictates when you’re going to die,” Ansell, author of the 2021 book The Death Gap: How Inequality Kills, said in an interview with WTTW News. “We did a root cause analysis of people dying earlier in neighborhoods close to each other. At the root cause of this were things like structural racism and economic deprivation,” including a lack of access to healthy foods.

Ansell notes that on the West Side, this means higher rates of diseases where such access could make a difference. “Heart disease and cancer are the No. 1 and 2 causes of death,” he told Fox 32 Chicago. “And fresh food is critical."

Bassett leads a Rush program that delivers fresh food to residents on an ongoing basis. But Rush spearheads other efforts that address food insecurity, including one in which Rush staff check that patients have food resources before they leave the hospital and a new program that will send some patients home with food after visiting their primary care doctor.

For now, food giveaways are a stopgap measure. “We’re able to provide some short-term relief until there is a long-term solution, which is a fully staffed, well-stocked grocery store,” Ansell told the Chicago Sun-Times.

West Garfield Park has one grocery store, but it still misses the vacant Aldi store at 3835 Madison St.

The Garfield Park Rite to Wellness Collaborative is working with the city to find a new grocery for the property. The Chicago City Council has authorized Mayor Lori Lightfoot to spend $700,000 to acquire the property, which Aldi has put up for sale, the Chicago Sun-Times and other news media reported. The property is still on the market.

Supporting local business

When a new grocer is found, it will need a viable business plan, Ansell said. Grocery stores have very small profit margins, and grocers need the support of the community and institutions, such as the hospitals that belong to West Side United, including Rush, he added.

Bringing a grocery store back to the vacant property is one part of ongoing work to improve the entire Madison Street corridor, a project led by the Garfield Park Rite to Wellness Collaborative. The group recently converted a vacant lot to an outdoor roller rink at Pulaski and Madison.

As part of its goal to improve the health of the neighborhood, the group started a wellness campaign that offers fitness, parenting classes and nutrition education. Its larger goal is to open a wellness center that would offer health care services, mental and behavioral health services, a recreation and fitness center and daycare services, according to T.J. Crawford, executive director of the collaborative.

“The Garfield Park Rite to Wellness Collaborative is an example in the city of hope,” Ansell told WTTW. “This is about real investment in a neighborhood that will allow for economic growth and development — a vital infusion of things which are at the heart of health.”